Our brother Arturo DeHoyos, Great Archivist and Great Historian, following his visit to the Supreme Council of Romania, sent for the Romanian Scots brothers a short summary of his last appearance "Ettiene Morin. From the French Rite to the Scottish Rite" written together with Josef Wäges, 32°, Board Member of the Scottish Rite Research Society, work currently being translated into Romanian.

The early origins of the "Royal Secret Order" - the system of Freemasonry which became the parent of the Scottish Rite - are discussed in my recent book Étienne Morin: From the French Rite to the Scottish Rite (2024), which I wrote together with Josef Wäges. My presentation today is a brief summary of some of the main points in our study and helps explain why the Symbolic Degrees of the Scottish Rite were created.

It is important to note that although we have discovered many new things, there are still aspects that require further research. For example, we still do not know when and where Etienne Morin, the creator of this system, was initiated as a Mason. However, for now it is enough to know that the Royal Secret Order was his brainchild, and that he owed much to the "happy accident" of being taken prisoner during the War of the Austrian Succession (1740-48) and again during the War of Seven Years (1756-63). The courtesy extended to him as a Freemason made it possible for him to receive the degrees and authority which he later used to spread High Degree Freemasonry.

First, however, let's take a brief look back at our Masonic origins to understand how these higher degrees developed.

Freemasonry early[1]

After the collapse of Roman society in Britain in the mid-5th century, Anglo-Saxon architecture consisted of a relatively simple style until the Norman Conquest in 1066. There is no evidence that any Roman Collegium or sophisticated building technology had persisted after withdrawal. Anglo-Saxon buildings were generally constructed of wood and clay with thatched roofs. After the Battle of Hastings, defensive structures were built - primitive castles made mainly of earth and wood. Although easy to build, they were vulnerable to the elements. Experimentation with new building techniques led to the development of superior stone structures that replaced earlier forms. The new fortresses not only protected borders, but helped define geographic regions. Many of these castles were granted to lords and nobles who acted on behalf of the king and administered his policies. Thus, castles also became important centers for government. Similarly, the Church improved its structures,[2] so that the stacked stone and mortar buildings were replaced by a more sophisticated and permanent stonework. Such improvements stimulated the development of society.[3]

The word "mason" (n.tr. "freemason") dates from after the Norman Conquest and was consecrated in the 12th century. It probably comes from Old French and means "to make or build".[4] The earliest known use of the word "Freemason" appears in a document dated 1325[5]. Even in their earliest uses, the words freemason and freemason they were interchangeable. Early English documents, spanning hundreds of years, make no distinction, and both words often appear in the same paragraph. The original use of the word in all its forms, "freemason"freemason"), "freemason" (n.tr. "freemason") and, finally, "freemason" (n.tr. "freemason”), probably comes from one of two sources. Substantial evidence supports the idea that he was referring to the cutters and setters of rough stone, "a homogeneous, fine-grained sandstone that can be worked equally in any direction".[6] A medieval "master mason" was distinguished from "rough masons, who only make walls".[7] This suggests that the term "free-stone-mason” was contracted to “freemason„.

However, a competing theory suggests that privilege, rather than ability, was responsible for the naming:

"A man admitted to the privileged position of master in a trade guild or as a citizen in a city became 'free' of the respective guild or city, becoming a "freeman" in the sense of be free to enjoy certain rights, and hence to appoint a fully qualified Master Mason a freemason or one freemason it was just a small step."[8]

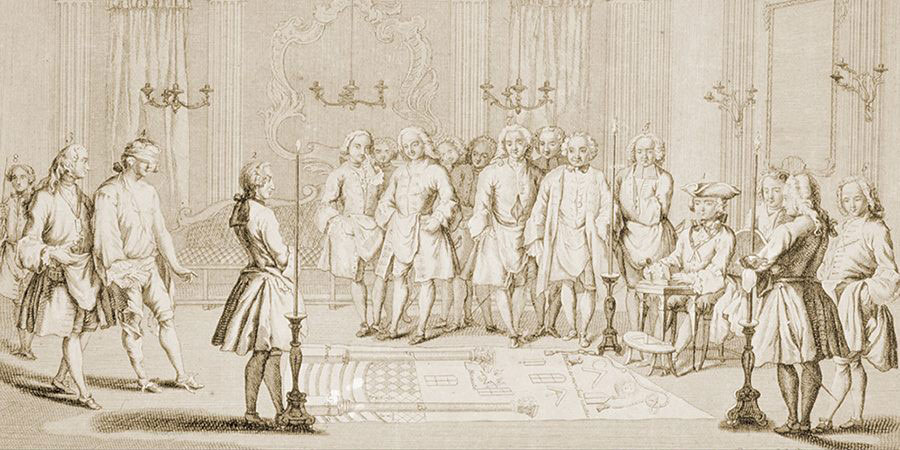

Assembly of Freemasons for the Reception of the Apprentice (1745) – ARTURO DE HOYOS Collection

Classical medieval apprenticeships had both "guild pride, as much and as and guild secrets. By learning a trade from an expert, pride in the trade was passed on to the next generation of professionals."[9] These "mysteries" or secrets of the guild were not secret in the modern sense of the word, but rather referred to the practice of a trade[10] specific.

Thus, there were not only "Masonic secrets", but also mysteries of barbers, shoemakers, coopers, grocers, mercerists, winemakers and others. Although English "guilds" existed as early as around 950, there is no evidence of Masonic guilds until 1356-1376. However, even before this date, the "mysteries" of medieval constructions were preserved through the use of symbolic images.[11]

In 1583, King James VI of Scotland appointed William Shaw "Maister of Wark" to the top of his country's master masons.[12] In 1598 and 1599, Schaw issued statutes that introduced many concepts that survive in Freemasonry today. Together with the Old Duties, they formed a basis of government that influenced modern Masonic Grand Lodges. The Schaw statutes defined a hierarchy of "wardens, dekynis and mastery in all that concerns their work".

Masonic lodges were to be presided over by a "General Warden", while William Schaw himself presided over all the Masonic Lodges in his country, as Grand Masters do today in most parts of the world. A close reading of the Schaw Statutes also shows that originally there were only two classes of Masons, namely "prentice” and “fellow of craft„.

First Grand Lodge and the degree of Master Mason

Following the Great Fire of London in 1666, craftsmen were called upon to help rebuild the city, and it is likely that during the rebuilding, the masons shared their legends and traditions with each other. The transition theory suggests that, following Reconstruction, masons left London and activity declined until Freemasonry was "revived" on 24 June 1717, when four London lodges[13] they met at the Goose and Gridiron Ale House and elected a "Grand Master."[14] This act has often been regarded as the formalization of non-operative Freemasonry, although some scholars[15] suggests that the meeting, called the "Grand Lodge," was rather a "Quarterly Communication" and was merely the continuation of a discontinued practice. For this reason, certain authors suggest that a specific date cannot be stated for the institutionalization of speculative freemasonry.gentlemen's masonry"). Other historians note that the origins of modern Freemasonry are more complex and should be examined in the wider context of contemporary cultural, political, religious and scientific developments and influences.

Thus, when the Grand Lodge of London and Westminster (later called the First Grand Lodge of England) was organized in 1717, it continued the ceremonial practices of operative Masons,[16] , but with a different philosophical approach. The creators of this Grand Lodge wanted an organization in which they could promote their ideals.[17] In simple terms, the founders of the Grand Lodge system took over the older system like well-intentioned pirates.

The New Grand Lodge continued the early Masonic structure, with the two levels of membership – Apprentice and Journeyman – both titles being borrowed from Scottish Freemasonry. As the fraternity developed, changes were introduced. Levels of membership have been referred to as "grades" since 1723.[18] We have very little information to explain exactly how this happened, but we also know that by 1725 the material had been rearranged to formalize the three degrees as they are known today.[19] The original Apprentice material was split to create a new Journeyman degree, and the material from the former Journeyman ritual was transformed to create the Master Mason degree.[20] The earliest known conferral of the Master Mason degree took place on May 12, 1725, when brothers Charles Cotton and Papillon Ball "were regularly made Masters."[21] One of the most obvious persistent artifacts of this transition was the retention of the term "fraternity points"points of fellowship”) in English Freemasonry – words that originally referred to the degree of Journeyman. Some ritualists later changed this term to "points of mastery"[22] (n.tr. in the text " points of mastery”) or “points of Masonry”. As far as we know, the emergence of the Master Mason degree as a separate degree within the fraternity represents the emergence of the first "High Degree". This important fact extends the tradition of the High Degrees to near the beginning of the fraternal phase of Freemasonry.

THE EMERGENCE OF OTHER HIGH GRADES

Freemasonry is generally considered to have arrived in France in 1725, the same year that the Master Mason degree appeared in England. Soon after, other high degrees began to appear in England, including "Harodim", "Excellent Mason" and "Grand Mason".[23] Among the earliest and most important High Degrees was the "Lodge of Scottish Masons," which appeared about the year 1733. The Lodge conferring this degree had no warrant, and never paid for a charter, but was thoroughly regular. Apparently it existed only to confer High Degrees.[24] Interestingly, it met in the same building where the Grand Lodge used to meet.[25] Between 1733 and 1740 we have records showing that the degree of "Scottish Master Masons" was conferred on "regular" Master Masons in Bristol, England, in regular token lodges.[26]

High Grades, or hauts grades, became an important part of the early Masonic history of France, and their development and popularity eventually brought them to the New World with the coming of the French voyagers. As Freemasonry spread throughout the world, modifications to its rituals were gradually introduced at the local level. The basic themes of the three primary grades have remained relatively uniform, as have the ways of recognition. However, different lodges have retained or eliminated some practices and procedures while developing new ones. Just as the evolution of language and customs creates new cultures among peoples, so Masonic practices developed unique characteristics or expressions of ritual which later allowed them to be classified as separate "rites". In simple terms, a rite is the association of degrees intended for initiation or instruction, under a governing authority.

THE IMPORTANCE OF THE TRADITION OF THE SCOTTISH MASTER

Early Scottish Freemasonry was closely associated with the Master Mason degree and added to the story of Hiram Abif, the architect of Solomon's temple. Although the origins of the hiramic legend have not been satisfactorily discovered[27] The Graham Manuscript (1726) preserves a similar legend, with important differences. Instead of Hiram, his legend has as its protagonist the biblical Noah, the creator of the great ark.[28] After his death and burial, his three sons, Shem, Ham and Japheth, go to his grave to search for a valuable secret he had. They agreed that if they couldn't find the real secret, they would adopt a substitute. Arriving at Noah's grave, they find his body. They attempt to obtain the secret by lifting the corpse, first by grasping the hand in various ways, and finally by lifting it in a ritual embrace. The final touch they used was at elbow level and was the Scottish Master's touch.[29]

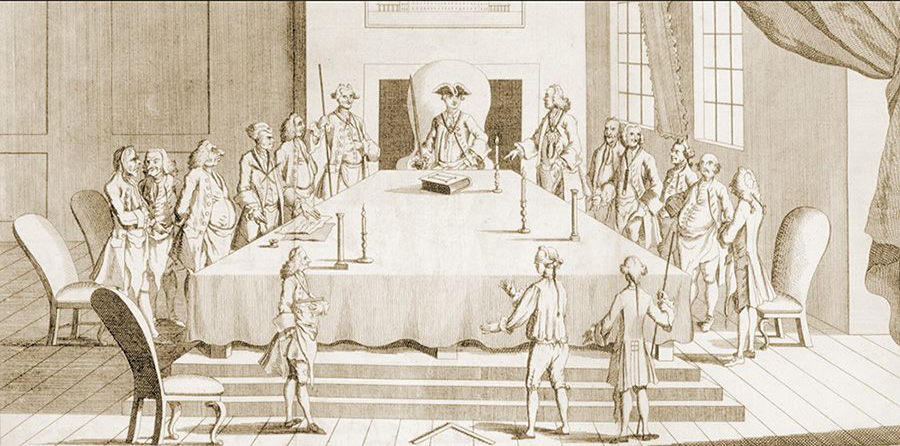

The Ceremony of Making a Free-Mason (1766) – ARTURO DE HOYOS Collection

Scottish Freemasonry was the ancestor of several Masonic rites, including the Royal Arch in the 1740s. The Royal Arch probably arose out of the Jacobite rebellion. Bona fide English Masons would not have wanted to be called Scottish Masters during this rebellion, so they kept the essential features of the ritual, introduced some changes and called it the Royal Arch. However, there are still many similarities between them.

The tradition of the Scottish master is why we have names like the Scottish Philosophical Rite and the Scottish Rite. A comparison of the first French and German copies, dating from the 1740s, shows us common elements which probably represent the traditions of the original English ritual. In fact, there are still many parts of the Scottish Master degree preserved in various rites.

As a merchant, Etienne Morin traveled between Europe and the New World. In 1744 he traveled from Bordeaux to Martinique. During this trip, he was initiated as a Scottish Master by Governor William Mathew at the Grand Lodge of St. John's, Antigua.[30] The following year he was the driving force behind the Ecossais Mother Lodge in Bordeaux and signed the regulations of the Lodge of Perfection of Scots.[31] As a promoter of the High Degrees, in 1761 the French Grand Lodge of Paris, together with a ritual body of the higher degrees, issued Morin a Grand Inspector's patent, "authorizing and empowering him to institute perfect and sublime Masonry in all parts of the world".[32] However, in 1762 he was taken prisoner and sent to England, where he met Earl Ferrers, who was Grand Master of the Grand Lodge of Moderns (ie the First Grand Lodge of England).

The English Grand Master approved Morin's patent issued by the Grand Lodge of France and declared him a life member of the lodges in England and Jamaica. This fact paved the way for Morin to operate anywhere in the Caribbean. From the time he returned to the Caribbean until his death, he founded 11 Blue Lodges under the authority of the Grand Lodge of France. These lodges used a number of different French rituals to confer the blue lodge degrees.

To exercise his increased authority, Morin took the High Grades he had received and began to restructure them, creating the Royal Secret Order. Although the Royal Secret Order was once believed to have been created by the Council of Emperors of the East and West, evidence suggests that it was Morin's idea,[33] , although it was not fully developed until after his death.

Most of the rituals of this Order were selected from a collection of bound manuscripts that Morin owned; this is now known as the "Baylot Manuscript". It included some of the most popular degrees practiced at the time.

In any case, in late 1762, Morin introduced the High Degrees to Kingston, Jamaica, and it was not until 1764 that the High Degrees were brought to North American territory, when they were established in New Orleans, Louisiana. At this early period, only a few degrees were conferred, and these were controlled by the blue lodges which were created by Morin through the authority he received from the Grand Lodge of France. At first Morin's blue lodges also conferred the Degrees of 4th Expert, 5th Elu, 6th Scottish Lodge of Perfection, 7th Knight of the East, and 8th Prince of Jerusalem.[34] As he improved his system, he removed the powers and privileges of the Princes of Jerusalem, who had once been the highest rank.

Around the same time, Morin empowered an enthusiastic Dutch Mason, Henry Andrew Francken, to establish Masonic bodies in the New World, including the United States.[35] On December 6, 1768, Francken appointed Moses Michael Hays Deputy Inspector General of the Rite, for the West Indies and North America.

Over the years, he continued to collaborate with Brother Francken and improve his system, until he died in November 1771. The story of the development of the Royal Secret Order as a 25-degree system is another story, which is somewhat complicated. Brother Josef Wäges and I are close to completing our next book, which will tell this story and include all the original rituals.

Morin's powerful influence had effects he could not have foreseen, as his system eventually led to the creation of the Scottish Rite in 1801. We know that following the Haitian Revolution, many of the French left the Caribbean and they returned home. After arriving there, some of them founded the Triple Unité Ecossaise lodge in Paris. This was, of course, after the creation of the Scottish Rite. Members of this lodge were prominent members of the Scottish Rite in France and created the first Scottish Rite for the symbolic lodge. The brothers most likely responsible for creating this ritual were Alexandre François Auguste de Grasse-Tilly, Pierre Mongruer de Fondeviolle and Germain Hacquet.

The manuscript of the ritual of this lodge is still extant and corresponds to the first printing of the blue lodge ritual of the Scottish Rite,[36] showing that they created it. It was based on a French translation of the exposition Three Distinct Knocks, published in 1760, and was supplemented with material from the rituals used in the Caribbean by Étienne Morin's lodges.

By creating this ritual, they ensured that some of the practices of those lodges would be perpetuated in the memory of ritual language and ritual procedure.

To put it bluntly, the Scottish Symbolic Rite of 1804 was a skillful synthesis of the traditions of Saint-Domingue Symbolic Freemasonry. Although it was created by a small group of people, its influence was far-reaching. The ancestral traditions, emanating from the French Rite, the Antients Rite and The Rite of Ecossais, had a wide impact, attracting many enthusiasts. This continues to happen today as the symbolic ritual of the Scottish Rite is the most popular type of ritual in the Masonic world; it is practiced in more countries than any other form of Symbolic Freemasonry. Thus, even if we ignore the High Degrees that became the Royal Secret Order – and later the Scottish Rite – this ritual of the blue degrees, which was created by those influenced by the work of Stephen Morin, remains a legacy of his boundless energy and passion unfettered in the pursuit of Masonic excellence.

Translation and adaptation, Alexandru-Răzvan Jeciu

Notes

[1] This summary it omits many important events and facts, which should be studied. On the development of Freemasonry, see, for example, Robert F. Gould, Concise History of Freemasonry (New York: Macoy Publishing, 1924); Douglas Knoop and GP Jones, The Genesis of Freemasonry: An Account of the Rise and Development of Freemasonry in Its Operative, Accepted, and Early Speculative Phases (Manchester University Press, 1947); Bernard E. Jones, Freemasons Guide and Compendium, rev. ed. (London: Harrap, 1950, 1956); David Stevenson, The Origins of Freemasonry: Scotland's Century, 1590-1710 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001); David Stevenson, The First Freemasons: Scotland's Early Lodges and Their Members (Aberdeen, Scotland: Aberdeen University Press, 1988); Richard Berman, The Foundations of Modern Freemasonry: The Grand Architects – Political Change and the Scientific Enlightenment, 1714-1740 (Sussex Academic Press, 2012).

[2] Guy Points, An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon Church Architecture & Anglo-Scandinavian Stone Sculpture (Rihtspell Pub., 2015) is a simple but informative introduction to the subject.

[3] An extremely interesting text on the development of Anglo-Saxon society, which also examines architecture, is John Blair, Building Anglo-Saxon England (Princeton University Press, 2018).

[4] Carl Darling Buck, A Dictionary of Selected Synonyms in the Principal Indo-European Languages (University of Chicago Press, 1949), 538; Robert Claireborn, The Roots of English (New York: Times Books, 1989), 158. In a different opinion, George Bullamore, Ars Quatuor Coronatorum [hereinafter AQC] 38 (1925), observed that the term mason arose when chisel work came into use in English architecture. He suggested that it might be related to the mazo, "a mace [which] was originally a club of any kind". Therefore, the author suggests, those who used these tools were masons.

[5] Reginald R. Sharpe, ed., Calendar of Coroners Rolls of the City of London AD 1300-1325 (London: Richard Clay and Sons, Ltd., 1913), 130-31.

[6] James Geikie, Structural and Field Geology (New York: D. Van Nostrand Co., 1905), 60.

[7] From Sir Thomas Elyot's Latin Dictionary (1538), quoted in GG Coulton, Art and the Reformation (Oxford: Basil Blackwell & Co., 1928), 183.

[8] stevenson, The Origins of Freemasonry (1988), 11. Emphasis added. Bernard E. Jones preferred this view and notes: “Versions of old revised documents for Scottish lodges may include the word, but only as an echo of English usage. Where the old English operative documents refer to a "Freemason", the Scottish documents refer to "a Mason". The Lodges of Edinburgh and Kilwinning did not use the speculative term 'Freemason' until some years later than 1717." –Bernard E. Jones, Freemasons' Guide and Compendium rev. ed. (London: Harrap, 1950, 1956), 124-25.

[9] Charles Sides and Ann Mrvica, Internships: Theory and Practice (Routledge, 2017). See also Mary Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400-1200 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), 29.

[10] Knoop and Jones, The Genesis of Freemasonry (1947), 41-44; Bernard E. Jones, Freemasons' Guide and Compendium (1956 ed.), 56-68.

[11] Mary Carruthers, The Craft of Thought: Meditation, Rhetoric, and the Making of Images, 400-1200 (Cambridge University Press, 2000), 29.

[12] On the growth and development of Freemasonry in Scotland, see David Murray Lyon, History of the Lodge in Edinburgh (Mary's Chapel), no. 1. Embracing an Account of the Rise and Progress of Freemasonry in Scotland (Edinburgh: William Blackwood and Sons, 1873; reprint ed.: Gresham Publishing Co., 1900); David Stevenson, The Origins of Freemasonry: Scotland's Century 1590-1710 (Cambridge University Press, 1988); David Stevenson, The First Freemasons: Scotland's Early Lodges and Their Members (Aberdeen University Press, 1988)

[13] The four original Lodges were (1) At the Goose and Gridiron Ale-house in St. Paul's Churchyard; (2) the Crown Ale-house in Parker's Lane, near Drury Lane; (3) The Apple-Tree Tavern in Charles Street, Covent Garden; (4) Rummer and Grapes Tavern in Channel Row, Westminster.

[14] James Anderson, The New Book of Constitutions of the Antient and Honorable Fraternity of Free and Accepted Masons (London: Casar Ward and Richard Chandler, 1738), 109-10. This was the title given to the second edition of Anderson's famous work, The Constitutions of the Free-Masons (London: William Hunter, 1723).

[15] JAM Snoek, “Researching Freemasonry; Where are we?" Journal for Research into Freemasonry and Fraternalism. 1.2 (2010), 227-48.

[16] When Dr. John Theophilus Desaguliers visited Edinburgh Lodge on 24 August 1721, was found to be "properly qualified in all aspects of Masonry" and was received "as a Brother into their society". John R. Dashwood, trans. and Harry Carr, ed., The Minutes of the Lodge of Edinburgh, Mary's Chapel, No. 1 1598-1738 (London: Quatuor Coronati Lodge 2076, 1962), 269-70. For an excellent study of this important period, see Christopher B. Murphy and Shawn Eyer, eds., Exploring Early Grand Lodge Freemasonry (Plumbstone, 2017).

[17] Berman, Architects, 17

[18] The earliest known use occurs in the unveiling of the Post Boy (1723): "Q. What's your name? A. Base or Capital, according to my Degree.". For the full text, see S. Brent Morris, "The Post Boy Sham Exposure of 1723", Heredom 7 (1998): 34.

[19] Christopher Powell, "The Hiramic Legend and the Creation of the Third Degree," AQC 134 (2021), 91-92.

[20] Lionel Vibert, "The Evolution of the Second Degree," The Collected Prestonian Lectures. Volume One, 1925-1960 (London: Quatuour Coronati Lodge 2076, 1965; reprint ed., Lewis Masonic, 1984), 47-61.

[21] Charles Cotton was made a Mason on 22 December 1724, and later became a Fellow Craft (date not specified). RF Gould, “Philo-Musica et Architectura Societas Apollini. [A Review.]', in AQC 16 (1903), 112-28.

[22] For example, the 1801 revision of Friedrich L. Schröder, used by the lodge Absalon zu den drei Nesseln (Hamburg), uses the five points of mastery (five points of the Championship).

[23] Bernheim, "Did Early 'High'...", 96-97

[24] John Lane, "Masters' Lodges," AQC 1 (1888), 167-75

[25] "For a long time after the revival of Freemasonry in 1717, Masonic lodges continued to meet, as they had done before that time, in taverns. Thus the Grand Lodge of England was organized, and, to use Anderson's language, "quarterly communications revived," by four lodges, whose respective places of meeting were the Crown Ale House, the Apple-Tree Tavern, and the Rummer and Grapes Tavern. For many years the Grand Lodge held its quarterly meetings sometimes at the Apple-Tree, but mostly at the Devil Tavern, and the Grand Feast was held in the hall of one of the Livery Companies." -Albert G. Mackey, "Hall, Masonic," Encyclopedia of Freemasonry (Philadelphia: Moss & Co., 1873, 1878)

[26] Eric Ward, "Early Masters' Lodges and their Relation to Degrees," AQC 75 (1962), 131. At Bear Lodge in Bath, the degree continued to be popular for the next 20+ years: "An undated page of minutes belonging to the end of October or the beginning of November 1735 is entitled "The Lodge of Masters met extraordinarily and our following worthy brethren were made and admitted Scots Mast. Masons". Over the next twenty-three years, this degree was conferred at four more reunions, three of which were "extraordinary," on twenty-one other brethren. All the candidates, so far as can be ascertained, were Master Masons, some of very recent date. For example, the two visitors made Scottish Master Masons on 17 February 1756 had been initiated on 3 February and raised on 13 February in the same month." -PR James, "The Bear Lodge at Bath 1732-1785, Now the Royal Cumberland Lodge No. 41", in AQC 59 (1948), 69.

[27] rev. WW Covey-Crump researched the sources of the legend, without concrete results. See his work The Hiramic Tradition: A Survey of Hypotheses Concerning It (London: Masonic Record, Ltd., [1924]). It has also been suggested, without evidence, that the Hiramic legend derived from medieval "mystery plays", "morality plays" or "miracle plays". See Edward Conder, Jr., "The Miracle Play," AQC 14 (1901), 60-82.

[28] Robert F. Gould wrote that he "rejected as inconceivable the theory that the ceremonial of 1730 [the Hiramic legend] was introduced into Masonry after 1717" and that "the main point he wishes to establish ... is the moral certainty of ceremonial from 1730, being older than the Grand Lodge of England".

[29] The four touches correspond to the degrees: (1) on the finger, disciple; (2) from joint to joint, Fellow Craft; (3) on the wrist, Master Mason; (4) in elbow, Scots Master.

[30] Le Quarre ou le parfait Elu Ecossais, Grand Collège des Rites Ecossais, 29-30.

[31] Alain Bernheim, "Notes on Early Freemasonry in Bordeaux (1732-1769)", AQC 101 (1988), 110-113; see especially 81-82. "Estienne Morin et l'Ordre du Royal Secret", Acta Macionica (Brussels) vol. 9 (1999), 20.

[32] Since Charles Porset published the correspondence between Mathéus, Constant de Castelin and Fleuret de Turville (Bibliothèque Nationale de Paris, FM2 544, fol. 7-36) in Chroniques d'Histoire Maçonnique no. 48 (IDERM, Paris 1997), 10-47, the existence of Morin's patent can no longer be doubted.

[33] For arguments in favor of the view that Morin falsified his authority, see Alain Bernheim, "Une decoverte etonnante concernant les Constitutions de 1762," Renaissance Traditionnelle no. 59 (July 1984), 161-97; ACF Jackson, "The Authorship of the 1762 Constitutions of the Ancient and Accepted Rite," Ars Quatuor Coronatorum 79 (1984), 176-91. ACF Jackson, Rose Croix: A History of the Ancient and Accepted Rite for England and Wales rev. & enl. (London: Lewis Masonic, 1980, 1987), 46-54. For the opposite view, see Jean-Pierre Lassalle, "From the Constitutions and Regulations of 1762 to the Grand Constitutions of 1786," in Heredom 2 (1993), 57-88.

[34] Mrs. 104 D. LII. Haut Grades de l'Orient de Paris. Archives of the Grand Lodge of Sweden.

[35] The Albany body was only active for seven years and ceased to function entirely in 1774. See "The Original Minutes of Ineffable and Sublime Grand Lodge of Perfection of Albany, NY, from 1767 to 1774," in 1906 Proceedings of the Thirty-seventh Council of Deliberation for the Bodies of the State of Ancient Accepted Scottish Rite Northern Masonic Jurisdiction, USA, of the State of New York (Printed by Order of the Council, 1906), supplement, p. 130. The High Degrees of Albany were revived forty-six years later, in 1820, by Giles F. Yates, and came under the jurisdiction of the Supreme Council of Charleston . See Arturo de Hoyos, "The Supreme Council of the 43rd Degree," in de Hoyos and S. Brent Morris, Cerneauism and American Freemasonry (Washington, DC: Scottish Rite Research Society, 2019), 146-74.

[36] See Pierre Noël, Guide des Masons Écossais. To Edinburgh. 58\ Les grades bleu du REAA: genesis et développement (Paris: A l'Orient, 2006)